The Open Goldberg Variations, a project crowdfunded on Kickstarter, has recently released a new score and recording of J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations BWV 988 directly into the public domain. This means that both the recording and the score can be accessed, played, remixed and used in any possible way. This commendable effort has had considerable resonance throughout social media, blogs and has been covered by Wired UK magazine.

The recordings can be downloaded from the project’s site in several formats, including a high quality FLAC version. The score is available as PDF at IMSLP or one can access a digital edition on the MuseScore.com platform. They also prepared a free iPad app that marries the recording with the score.

The process of production of the edition and its digital publication are particularly interesting. They are certainly pioneering and they have succeeded in bringing issues of digital publication of music to the attention of a more general public. This said, in this post I will deconstruct some aspects of the project to see how much of this can be relevant to an academic context.

There are already editions and recordings of the Variations in the public domain, but the project is the first of its kind to produce a new rendition to go straight into the public domain. This opens up countless opportunities for anyone to create new content, new art, new editions and whatnot based on this work. This is great, though the “setting Bach free” rhetoric that has pervaded the project since its early stages needs to be taken carefully. Someone else already pointed out that it’s not the Variations that have been set free, but a specific performance of it; likewise, the score is one specific edition of the text.

The score is not meant to be a critical edition, so there isn’t any information about which sources have been used, what has been corrected, normalized or modernized, etc. The editorial work is attributed to Werner Schweer and the text went through two public “peer-review” phases. This was done through the MuseScore.com platform, which allows users to leave annotations on published scores (sort of like a Flickr for sheet music). Comments were left on an already drafted edition of the text, so practically all of them were concerned with layout and legibility of the notation, not with the accuracy of the editorial work (the comments can be seen here). The issue of variance across sources has occasionally come up, but was dismissed with the principle that anyone is free to create different versions:

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that the now finalized official Open Goldberg Variations version is more likely to be distributed that any derivative edition.

To typeset the score, the editor has used the open source desktop application MuseScore, of which he is the lead developer. This is a very good piece of software (I use it regularly), though the editor/developer (an interesting position to be in, more on this some other time) was required to greatly improve it to cope with the complex notation of the Variations that includes abundant cross-staff beaming and non-standard baroque ornaments. As a result, MuseScore is probably one of the few free score editors that is able to deal natively with schleifer, doppelt-cadence, etc.

This makes me think of an old topic in the debate around scholarly digital editions: where are the tools for producing them? Many have argued, and I second them, that each historical text will have specific requirements that are likely to make a generic tool feel like a constraint rather than a facilitation. The editor/developer of the Open Variations must have realized that each repertoire and even each single piece, will have specific requirements that reach the limits of the tool.

recording almost note-by-note

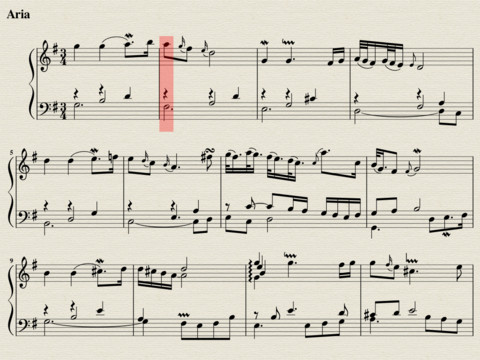

The score has been produced with a digital-centric workflow, so that both printed and digital publications of the work are possible. The digital score has substantial knowledge built-in, which allowed developers to come up with a few interesting things for its publication on a digital medium (website, iPad app, etc.). Such a score is able to “play” itself, but more interestingly it allows a certain fluidity of layout; in the iPad app, for example, one can seamlessly switch from portrait to landscape orientation for better readability. The score also “knows” the pitch and duration of each note and the app has been programmed to highlight each note when it’s played in the recording (read more about the technology behind this here).

But what makes this stand out from a printed publication? The iPad app in particular is more usefully targeted to listeners than performers: the alignment with a pre-existing performance is probably of little relevance to a performer and the page-turning system is awkward.

Finally, who are the readers that need note highlighting when reading and listening? Those trained to read music notation will not need it. The introductory text to the app often mentions the “fans” of the Variations, which can easily be both musically trained or not, so the highlighting may have some pedagogical use. Mostly, though, the highlighting shows what a “smart” score can do (or an e-score, or something else, a name for this new thing hasn’t really been established yet!).

Could there be more, though? I would say yes; the Variations’ app still presents a very static, print-like text, with a wow-inducing feature. A publication targeted to listeners (such as this one) could be a lot more informative, give access the editorial work behind the text, historical notes, show suggested (even better contested) resolutions of ornaments, etc. If it were to be targeted also to performers, the situation would get more complicated.

The Open Goldberg Variation project shows that the technology for digital editions of scores exists. The interest that the project generated (be it for its Open Source ideas, the open peer-review process, or the quality of the recordings) shows that there is also an interested audience. Is there interest in academia to take a step into this innovative market?

What do you think? Is this the direction for digital music publishing both scholarly and not? Would you use this edition for your work or performance?